Never Draw Another Org Chart

An organization chart ("org chart") is a tool to communicate data, not a drawing. Org charts communicate information about items and the hierarchical relationship between items.

There are many types of charts, diagrams, and graphs. Not all are for hierarchies. The sole purpose of an org chart is to show a hierarchy.

Hierarchy is Essential, Inevitable, and Unavoidable

The term "hierarchy" gets a bad rap. Managers and employees like to say their company does not have hierarchical structure. Human Resources departments invent words like "matrix", "flat", "team" to describe their organizations.

The Law Requires Organizational Hierarchy

Criticism of hierarchy misses the origin of the formal organization. An organization is a legal entity. True, there are unincorporated and informal "organizations," but they do not generally run businesses. Legal entities exist by virtue of the laws that allowed their creation. There are many types of legal entities. Regardless of type, legal entities are formed. People form legal entities.

The type of legal entity and the jurisdiction where the entity is created determine what those people are called. Incorporators, members, and partners are common terms. Those people create a legal entity in a national, state, or provincial jurisdiction. Yes, there are exceptions to all these statements, but even the exceptions prove the point.

When people create legal entities, they establish a record of who has authority to represent the entity. That record might be obscured and limited in the case of a registered agent who is empowered to accept service of process for the entity. Whether public or private, certain people have authority to bind the organization through contracts and to act on behalf of the organization.

Entity founders can designate or nominate others to manage on the organization's behalf. When they delegate their power, the hierarchy is established. The people who control the legal entity can modify or revoke the power of subordinates.

Consider two examples, both from the United States because the majority of businesses globally are one of these two types: a corporation and a limited liability company.

Corporations - the OG of hierarchy

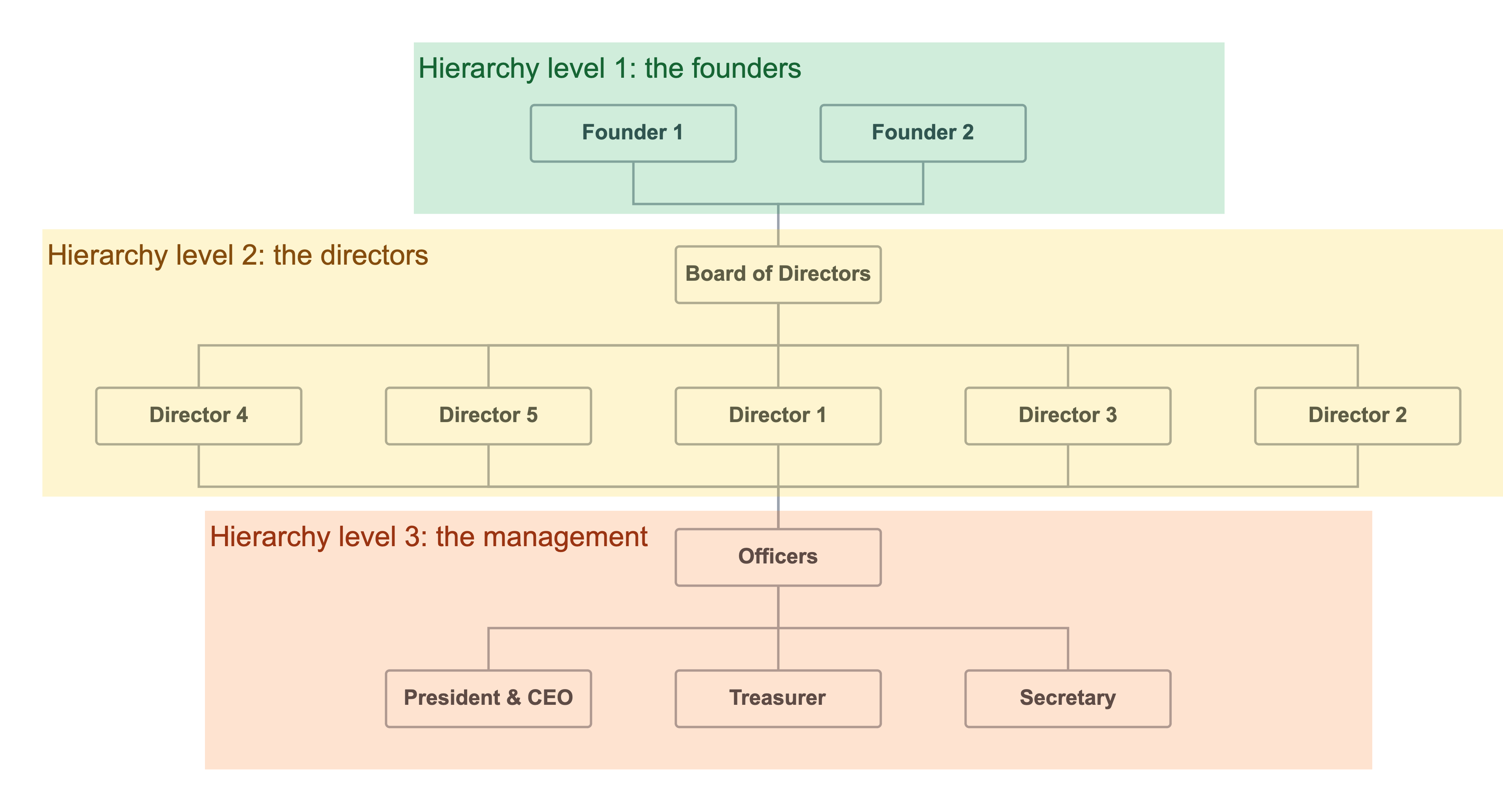

States in the US authorize people to form corporations pursuant to each state's corporate law. The majority of states have adopted a form of the Model Business Corporation Act (MCBA), maintained by the American Bar Association. Admittedly, important corporate law states like Delaware, New York, and California have not adopted the MCBA, but these general principles still apply.

The organizational documents that create the corporation spell out who has authority to act for the corporation (agents). The founders of a corporation are called owners, shareholders, stockholders.

The most common structure of a corporation is for the owners to form a Board of Directors. The owners vote for people to serve as directors to represent the interests of owners. Directors appoint officers to manage the business of the corporation.

Voila, there is the hierarchy at the core of the corporation.

The organizational documents (articles of incorporation, bylaws, shareholder agreements, and the like) spell out the officer titles and roles. The president and chief executive officer (CEO) occupies the apex of the officer hierarchy. The Board of Directors empowers the President and CEO to manage the daily operations of the business and to report on the results.

Do not confuse the apex of the officer team with the apex of the organization. The directors can remove the CEO. The owners can remove the directors. There is always a bigger fish.

As the person responsible for the business, the CEO needs help. The CEO creates managers. Managers need help performing the work of the business. Managers hire employees. This process, and the resulting structure, exists for small and large businesses in any jurisdiction. The tax status of the corporation is irrelevant. The scope, scale, and industry of the business are irrelevant.

What is relevant? The chain of agency from the owners to the directors to the officers to the managers to the employees matters.

An organization might call employees, "staff", "personnel", "team members", or "finklewonkers," but the fact remains that a person is empowered (maybe even obligated) to terminate another person's employment in a corporation.

LLCs are no exception

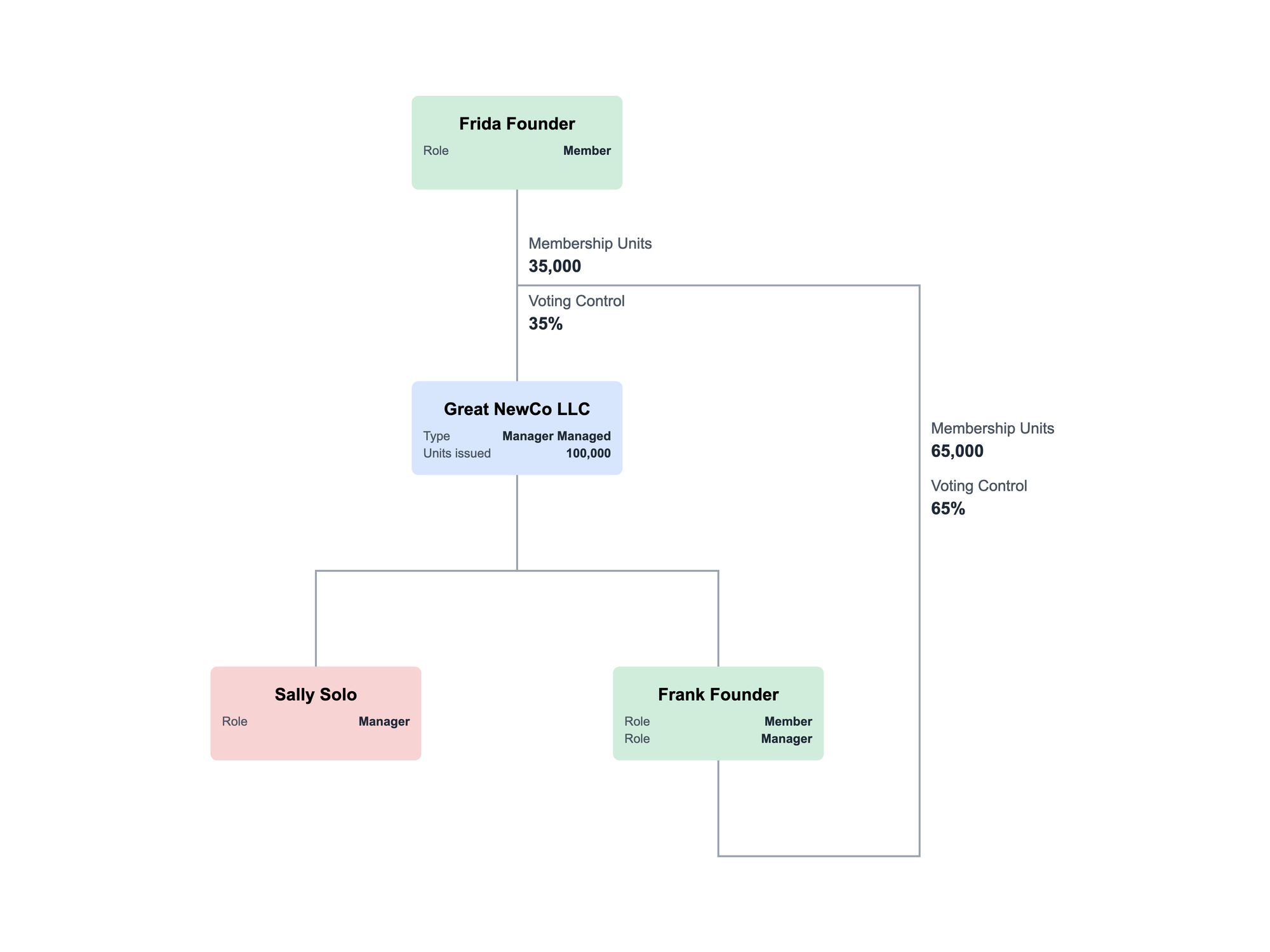

Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) have grown exponentially for combining favorable "pass-through" tax status with organizational flexibility. The Uniform Limited Liability Company Act is the popular base of most state laws on LLCs.

An LLC is a legal entity formed by people in a jurisdiction, like a corporation. The owners of an LLC are called "members," but the founders might use other terms.

There are two types of LLCs (ignoring variations like Series LLCs): member managed and manager managed. Both of these types result in a management hierarchy.

Member managed LLCs rely on the members (owners) to run the business operations. This structure skips the Board of Director step present in the corporate hierarchy. When the members invest one, some, or all of their members with the power to bind the organization, they create a hierarchy. Those members need help. They hire people to help operate the business. The members, acting as managers, are responsible to their fellow members for the health of the organization.

Manager managed LLCs rely on appointed people to run the business operations. This structure uses a structure similar to a corporation. The owners (members) designate a manager or managers to run the business. They might even call that manager the President and CEO. The manager's title is not important. What is important is that the manager's power comes directly from the LLC membership.

The manager might be a member of the LLC, but that does not mean the LLC is now a member managed LLC. The distinction is that the manager role is just that, a role, created by the membership. The members could fire the manager as a manager, but not as a fellow member.

What about B Corps, Cooperatives, ESOPs, or fill-in-the-blanks?

It is tempting to think that legal entity types designed for social benefits other than profits for owners escape the inevitable hierarchies of corporations and LLCs. There are two ways to respond to the temptation.

First, concede the exception. A legal entity type might not require a hierarchical structure flowing from founders/owners to directors to managers to employees. Congratulations. As a percentage of legal entities around the world, that type is a grain of sand compared to the ocean of legally recognized, commercially oriented organizations.

Second, exceptions are not exceptional. These types of legal entities add layers or structures, but do not radically alter the legal hierarchy.

An employee stock ownership plan (ESOP), for example, changes who owns and controls a company. The ESOP does not turn management into a collectivist structure where everyone is both a manager and an employee. Employees (more accurately the plan administrator) act as either owners or employees depending on the context.

Business Requires Organizational Hierarchy

The chain of agency from owners to directors to managers benefits the organization. People in businesses make consequential decisions. The hierarchy that passes authority and responsibility, when done well, keeps an organization running.

Managers assign work

Managers decide whom to hire, where to allocate company money, and whom to fire.

These decisions matter to everyone involved. The manager gets needed help. The hired employee gets work for which they are compensated. The organization earns more profit when more work is done.

When a manager assigns work to one employee rather than another, the manager exercises the business' authority and therefore spends the company's money.

The manager might consider employee preferences, skills, and available time, but the manager makes that decision. In an organization that is subject to a collective bargaining agreement, the employee might have certain rights and protections for the kind of work available. The management hierarchy still makes work assignment decisions.

Employee performance or business reversals might lead a manager to terminate an employee. Laws that govern the jurisdiction might constrain when, why, and how an employee is terminated. Within those constraints, the management hierarchy pursues the termination.

Managers organize people

Management hierarchy can reorganize itself below the President and CEO (assuming a corporate structure).

Reorganizations are comic in their frequency and ineffectiveness. Whether they succeed or not, managers, not employees, orchestrate reorganizations which shuffle the hierarchy.

Even temporary assignments to projects or teams get made by a manager directly or indirectly.

Managers set compensation

The most important test of the management hierarchy is that managers set compensation below those reporting to the Board of Directors or governance body. Employees can bargain for more compensation and better benefits. The ability and willingness of a manager to agree is shaped by the chain of hierarchy. If the owners, through directors and officers, want to support compensation changes, then changes happen.

Organization Hierarchy is Not Bad, it Exists

The point here is that ownership and management structures are hierarchical in business. No matter what terminology is used to soften the idea of hierarchy, the structure is central to legal entities.

Hierarchy is Data

A hierarchy has three, and only three, elements: a primary item, the connection, and a secondary item. This simple pairwise combination is flexible and scalable.

Hierarchies are Flexible

A variety of terms can describe a hierarchical relationship without changing the hierarchy structure.

| Primary | Link | Secondary |

|---|---|---|

| Owner | owns | Asset |

| Shareholder | owns shares of | Corporation |

| Member | owns interest in | LLC |

| Partner | owns partnership interest in | Partnership |

| Manager | manages | Employee |

| Director | directs | Department |

| Leader | leads | Team |

| Supervisor | supervises | Staff |

| Principal | governs | School |

| Chief | oversees | Division |

| Head | heads | Section |

| Commander | commands | Unit |

| Captain | captains | Crew |

| Executive | administers | Branch |

| Coordinator | coordinates | Program |

| Controller | controls | Process |

Hierarchies are Scalable

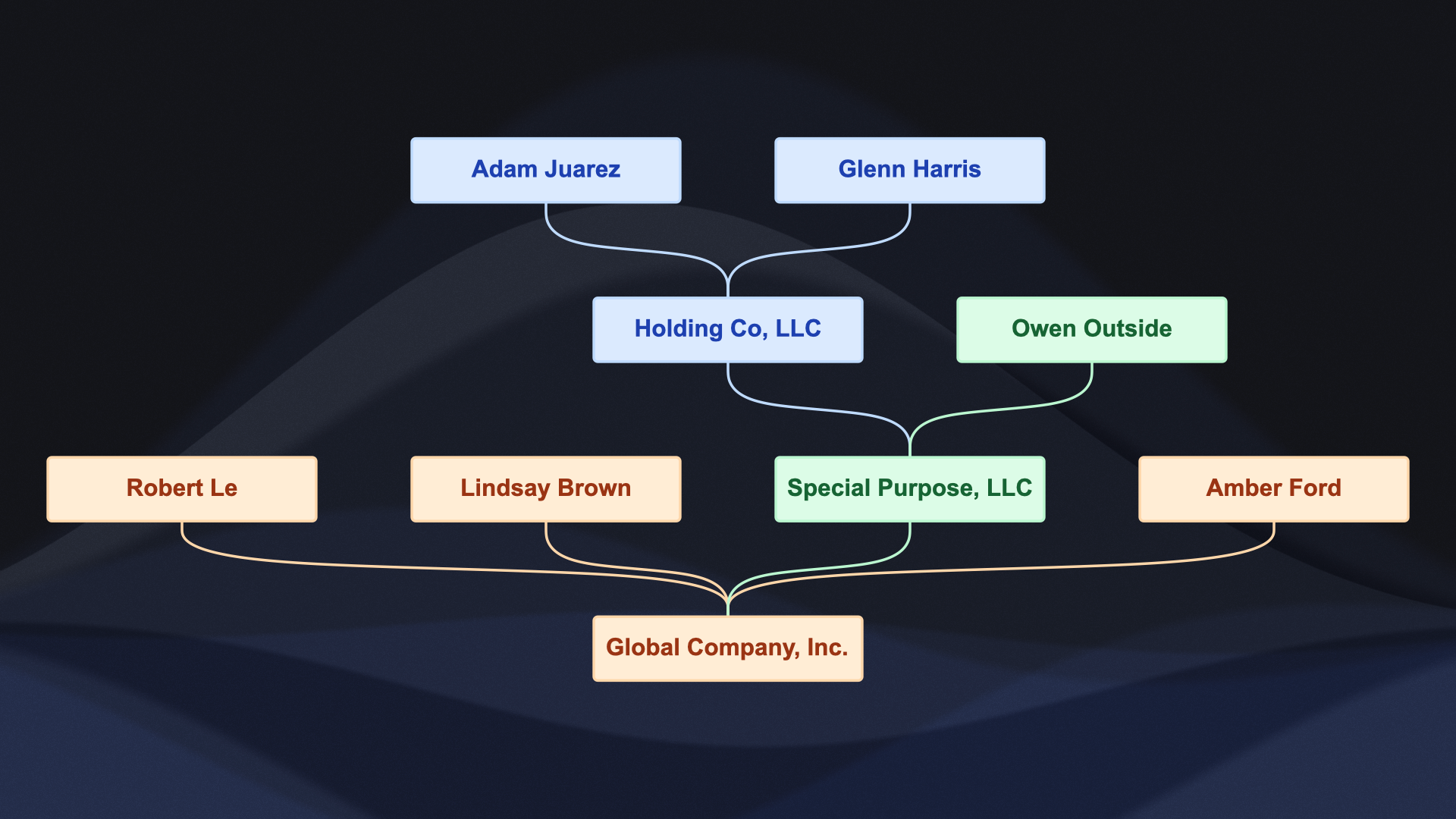

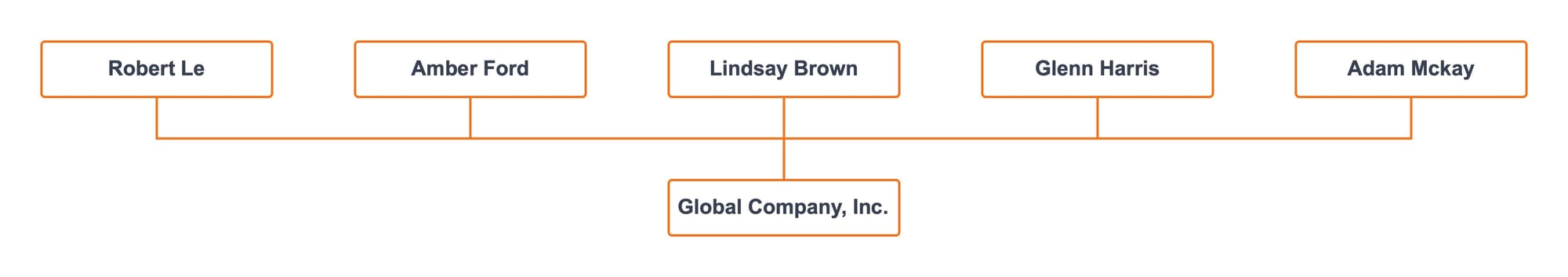

A large organization consists of many pairwise hierarchies linked together. Consider an example for the fictional Global Company, Inc.:

| Investments | Owners |

|---|---|

| Global Company, Inc. | Adam Juarez |

| Global Company, Inc. | Glenn Harris |

| Global Company, Inc. | Amber Ford |

| Global Company, Inc. | Lindsay Brown |

| Global Company, Inc. | Robert Le |

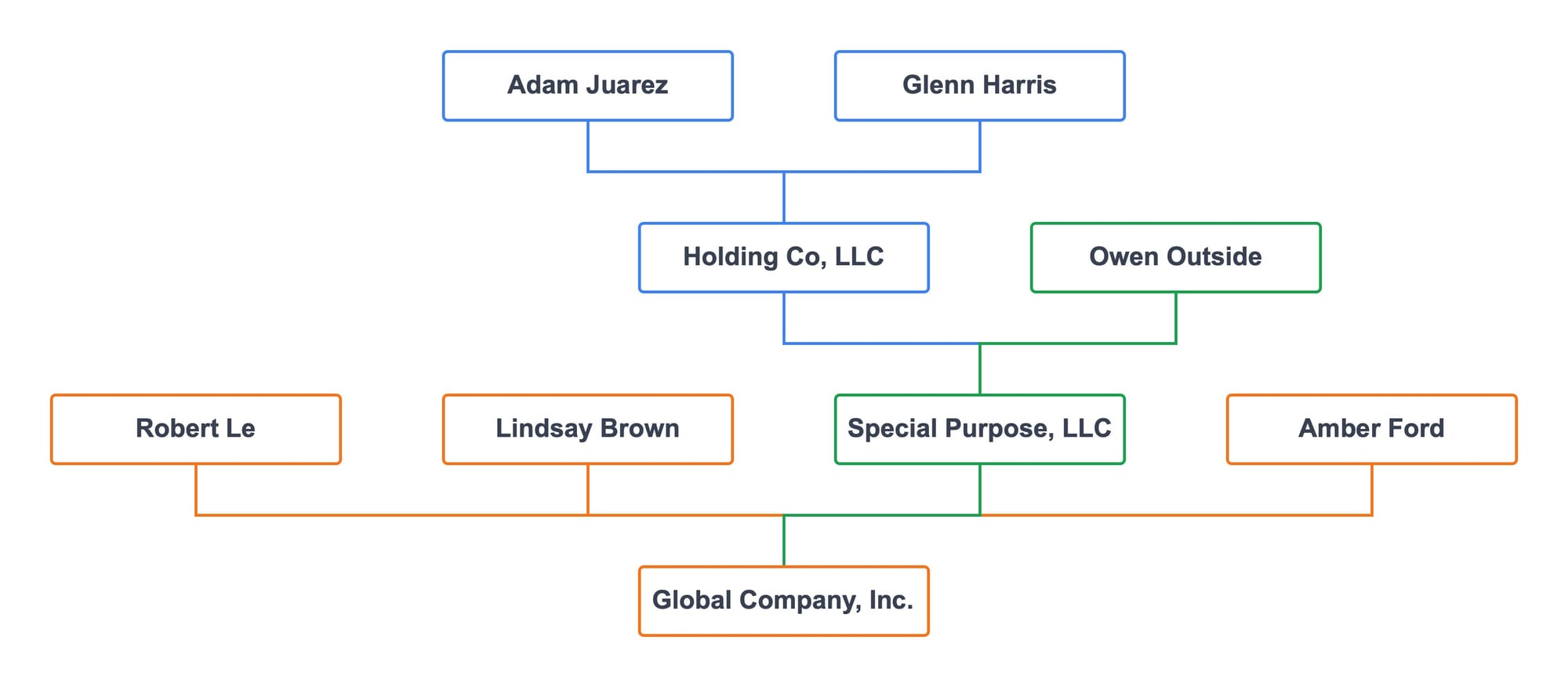

There are five pairwise hierarchies. The resulting chart meets our expectations.

Let's change the hierarchies. Adam and Glenn no longer own Global Co. Instead, they own Holding Co, LLC.

| Investments | Owners |

|---|---|

| Holding Co, LLC | Adam Juarez |

| Holding Co, LLC | Glenn Harris |

| Global Company, Inc. | Amber Ford |

| Global Company, Inc. | Lindsay Brown |

| Global Company, Inc. | Robert Le |

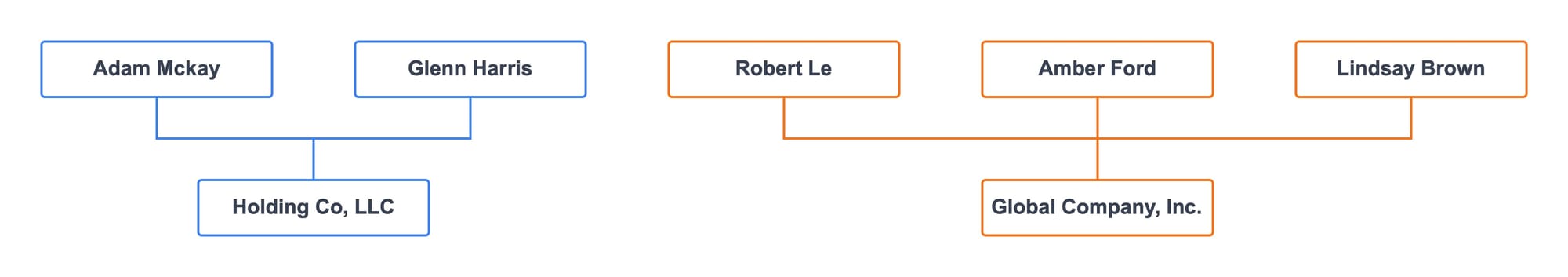

The chart now shows two separate legal entities with different owners. The entities have no connection, yet.

This is nothing remarkable. Two separate groups of single hierarchies exist side-by-side.

When we create one more hierarchy, Holding Co, LLC is an owner of Global Company, Inc., the power of linked hierarchies becomes clear.

| Investments | Owners |

|---|---|

| Holding Co, LLC | Adam Juarez |

| Holding Co, LLC | Glenn Harris |

| Global Company, Inc. | Amber Ford |

| Global Company, Inc. | Lindsay Brown |

| Global Company, Inc. | Robert Le |

| Global Company, Inc. | Holding Co, LLC |

That one additional relationship changed the structure of the company.

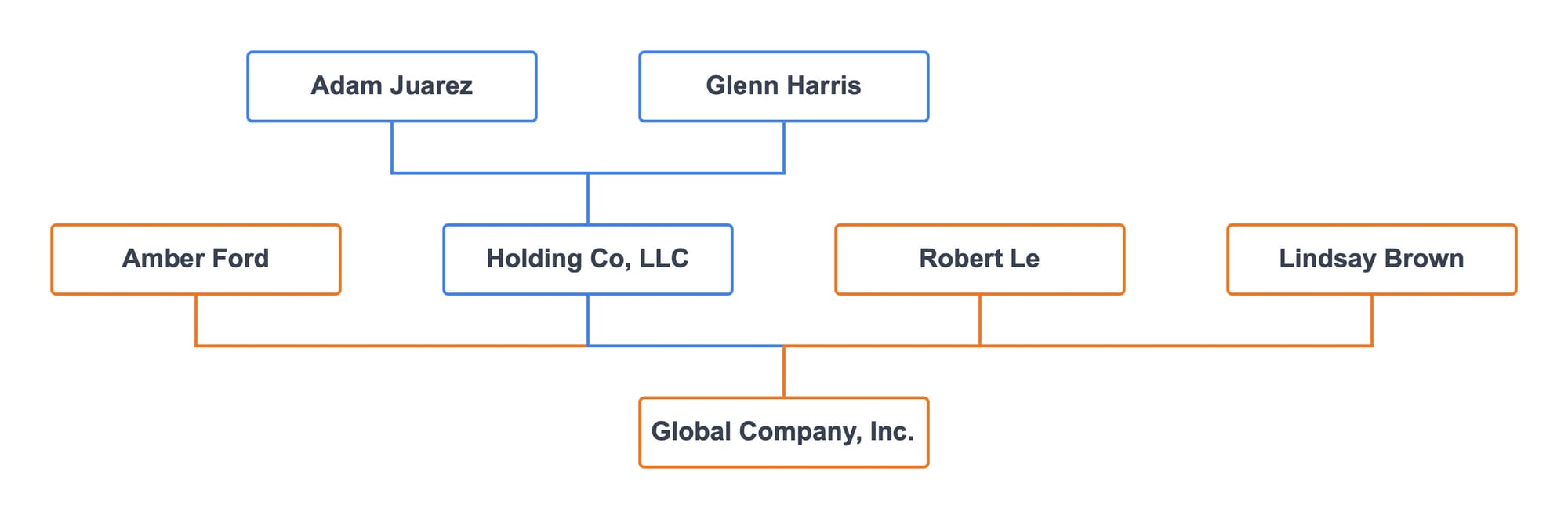

We can take the chaining of hierarchies further (there is no practical limit):

| Investments | Owners |

|---|---|

| Holding Co, LLC | Adam Juarez |

| Holding Co, LLC | Glenn Harris |

| Global Company, Inc. | Amber Ford |

| Global Company, Inc. | Lindsay Brown |

| Global Company, Inc. | Robert Le |

| Global Company, Inc. | Special Purpose, LLC |

| Special Purpose, LLC | Owen Outside |

| Special Purpose, LLC | Holding Co, LLC |

We inserted Special Purpose, LLC between Holding Co and Global Co. Accomplish this change with a new pairwise hierarchy and editing an existing one.

This chart is made with Lexchart for automatic organization charts.

Org Charts Show Hierarchy

An organization chart has a single purpose: show the hierarchy of an organization with clarity. Drawing a hierarchy chart by hand is time consuming, frustrating, and error prone.

7 Mistakes from Drawing an Org Chart

Without a focus on the org chart's purpose, an org chart creator (you and me) blunders into a chart making seven mistakes.

1. Moving Cards Around for Arbitrary Design Objectives

When the org chart creator does not like the look of chart at any point in the process, they drag one or more cards to a new location on the canvas.

Pushing objects around on an org chart might improve the look of the chart to one person, but not another. More important, moving cards obscures the meaning of the chart.

The better choice is to use automated layout that places cards in an optimal position, then leave the cards where they are.

2. Using Shapes for Data

In company structure charts, it is common to use different shapes to communicate the type of legal entity and/or its tax status in its tax jurisdiction.

This practice pervades legal entity charts. One might think it is a good idea. Don't be deceived.

Shapes cause more problems than they fix. First, the org chart creator knows what the shapes mean (in the creator's own mind). The chart reader, however, has no clue what the shapes mean.

Lawyers, paralegals, and tax professionals prepare charts routinely; executives and business managers read them occasionally. Your audience does not understand what you are saying with shapes.

"But the legend explains what the shapes mean..." The legend takes a lot of space on a fixed canvas chart. It gets separated from the chart, rendering it useless. Your audience must constantly look from the chart to the legend. Shapes increase cognitive load which obscures the chart's meaning.

The alternative to shapes is to use labels and data. Labels and data in the card communicate without doubt.

There is no doubt that Global Company, Inc. is a taxable Delaware corporation.

3. Duplicating Cards to Compensate for Horizontal Layout

From a mathematical viewpoint there are millions of possible layouts for an organization chart with more than 20 cards and links. The implication is that humans eventually get stuck when they need to place cards on a horizontal plane.

A common solution is to create a duplicate card and move it to a second position. The chart now contains an ambiguity. Is there one Global Co or two?

The solution is to use an automated approach that evaluates millions of possible layouts to position cards in an optimized way without duplication.

4. Crossing Lines

Human-drawn charts contain many line crossings because it is difficult to imagine a holistic layout that avoids them.

Unless the org chart contains five to ten items, avoiding line crossing is mathematically impossible for a human to accomplish in an ideal way.

The alternative, again, is to let a computer turn the spaghetti into neat lines.

5. Placing Cards at Incorrect Vertical Positions

Hierarchy implies vertical depth. That means the org chart creator has to place each card on the right vertical plane and consider all the links from above and below the card in question, for each card on the chart.

Let the computer do the work for you.

6. Using Multiple Lines Instead of Data

The relationship between two cards poses a unique challenge: how to describe the relationship? A multifaceted relationship complicates the question further.

The typical org chart creator adds a second link between the cards. What if there are three relationships, or more? These additional lines create more visual clutter, obscuring the purpose of the chart.

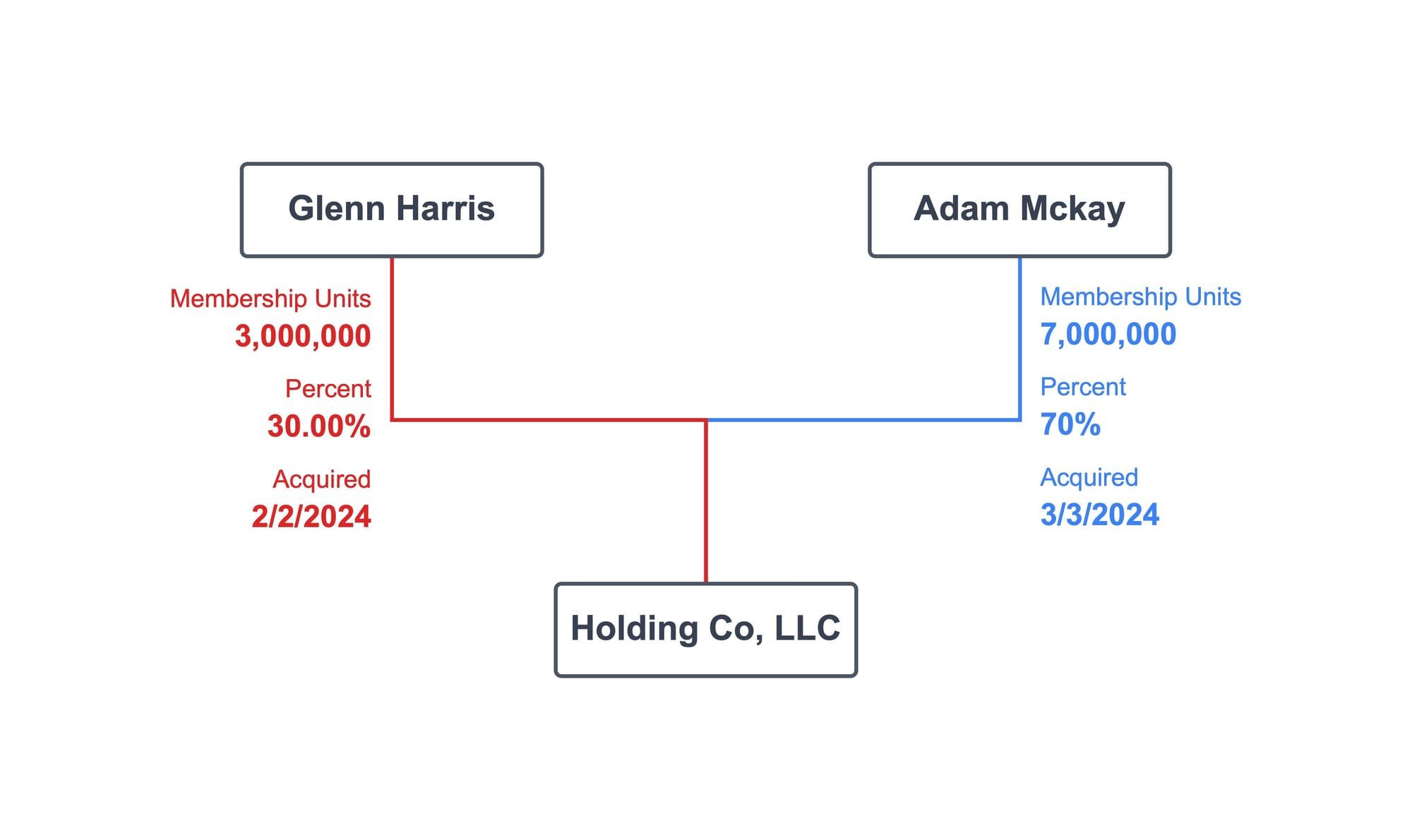

Use a single line to communicate that a hierarchy exists, then use labels and data to communicate all the facets of the relationship.

This chart shows how much of Holding Co, LLC each person owns and controls. It shows that the ownership relationships changed on 3/3/2024 when Adam acquired his interest.

7. Trapping the Chart in Fixed Canvas

A fixed canvas bedevils org chart creators. The best example of a fixed canvas is the PowerPoint slide. For charts of any size with labels and data, the fixed canvas makes a chart unreadable.

You have a choice:

- Break the chart into sections across slides to make the pieces readable; or

- Leave PowerPoint (a frightening idea indeed) for an infinite canvas.

Section a chart into subsections when that makes sense for your purpose. For example, showing a particular subsidiary and its children in an isolated chart is appropriate.

There are alternatives to PowerPoint. The important feature is to find one that has an infinite canvas. Use the infinite canvas to show the chart. Exporting the chart as an image in PowerPoint is possible, but defeats the benefit of leaving PowerPoint in the first place.

Automatic Org Charts Are Better than Drawn Charts

The benefits of an automated approach to organization charts are enumerated above. There are two major advantages:

- Unlimited space for unlimited people and entities with unlimited labels and data describing the chart; and

- Superior layout for a computationally intensive task that is not realistic for us mere mortals.

Automated org charts are fast and easy, assuming you let the application do the work for you.

Conclusion

Never draw an org chart. Use an automated tool, like Lexchart, to create a chart that communicates the hierarchy of an organization.